- October 10, 2017

By Eliza Roberts

Manager, Water at Ceres

Preliminary estimates for the costs of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria are in the hundreds of billions of dollars range—from disruption of business, to infrastructure and property damage, to crop losses. Each of the deadly storms hit agriculture especially hard, from cattle and soy in Texas, to citrus and sugar in Florida, to bananas and coffee in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico lost a staggering 80 percent of its crop value, according to its secretary of Agriculture, Carlos Flores Ortega.

Climate change didn’t cause the monstrous hurricanes, but a warming earth fueled their sheer destructive force. The food sector, which consumes 70 percent of our planet’s freshwater, is especially vulnerable to such extreme weather patterns that are the most visible and devastating hallmarks of climate change. Already, erratic precipitation and hotter temperatures are impacting crop yields and productivity.

With climate models predicting worse to come, food companies must better manage precious freshwater resources, and simultaneously shore up their resiliency against the impacts of an ever intensifying water cycle, from drought to altered rainfall patterns to flooding from turbo-charged storms.

Already, water risks in food production are escalating around the world:

- One-third of the world’s largest aquifers—mostly nonrenewable groundwater supplies used to feed crops—are being rapidly depleted in Saudi Arabia, India, Pakistan, northern Africa and California’s Central Valley. In India—where 90 percent of freshwater goes to feed crops—farmers have taken to the streets in violent protest over the government’s failure to solve the agrarian crisis in the face of prolonged drought; thousands of others have taken their own lives.

- Wheat production in the U.S. is down 9 percent this year, and the 2017 drought in southern Europe is reducing cereal production in Italy and parts of Spain to its lowest level in at least 20 years.

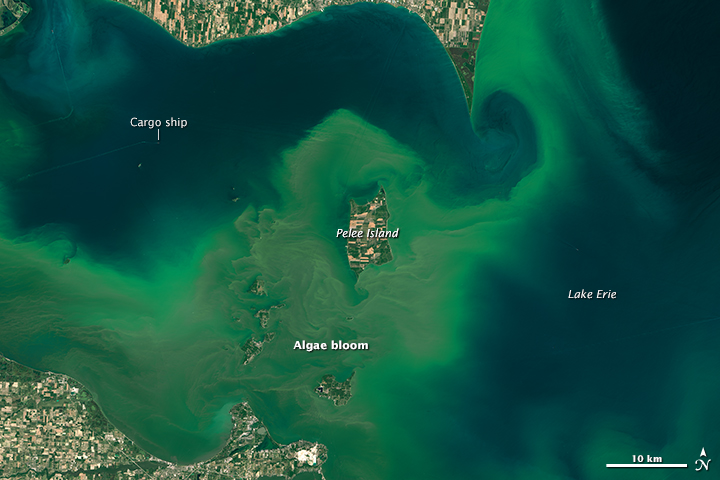

The meat industry, which consumes an enormous volume of water, is also responsible for huge wastewater and related pollution that result from animal slaughtering and processing. When manure is not disposed of properly, it can cause major toxic algae blooms. A Lake Erie bloom in 2014 left a half million people without drinking water. This year’s bloom is harming the regional economy.

Population growth adds further pressure. Water demands are expected to increase by 55 percent and food demands by 60 percent by 2050 when population will exceed nine billion. People everywhere will be eating more meat, fruits, vegetables and processed foods—all of which will put added pressure on the earth’s strained resources.

The implications for businesses that rely on agricultural crops are profound. A recent analysis by the investment research firm MSCI found that $459.2 billion in revenue is at risk for food companies from increasingly widespread water shortages for irrigation or animal consumption, and $198.2 billion is at risk from changing precipitation patterns.

Fortunately, not all food sector companies are failing to address the link between water, climate and their bottom line. Feeding Ourselves Thirsty, a benchmarking analysis by Ceres that scores the world’s largest food companies on their response to water risk, found that some corporate leaders are making progress—especially Coca-Cola, General Mills, Nestle, PepsiCo and Unilever—but the majority must do more to water-proof their businesses and protect and sustain water supplies. Here are a few examples of what companies are doing right:

- PepsiCo committed to work with its agricultural suppliers to improve the water-use efficiency of its direct agricultural supply chain by 15 percent by 2025 in high water risk sourcing areas.

- General Mills has set time-bound sustainable sourcing goals for each of its 10 major commodities sourced and clearly defines and measures progress against each goal using a dashboard on its website to track progress overall.

- Campbell’s uses a Supplier Sustainability Scorecard to capture environmental performance metrics, including water management, from 60 suppliers representing 80 percent of procurement spend. The data is used to benchmark suppliers, identify opportunities for engagement and evaluate future supplier relationships.

- Unilever co-invests one million Euros annually in training and equipment for its suppliers to accelerate the adoption of sustainable farming practices.

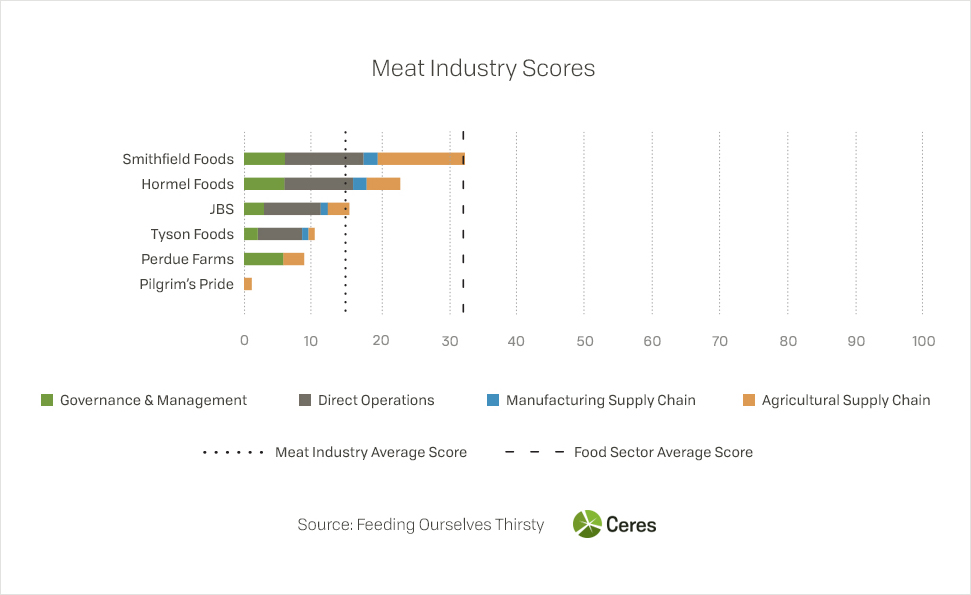

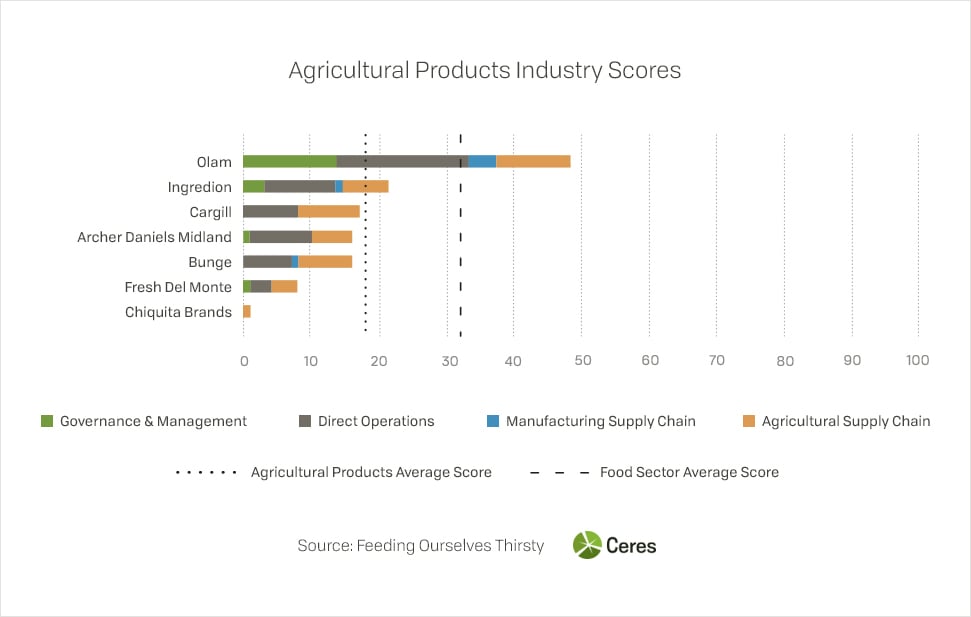

Even with these strong performers, however, the average score for the 42 companies evaluated in Feeding Ourselves Thirsty is only 31 out of 100 points. The meat and agricultural product industries in particular continue to lag woefully behind, demonstrating little investment in mitigating water-related risks, even though they have the highest exposure to them.

Starting today, the food sector must put into place water-smart plans to prepare for the inevitable. Companies need to assess their supply chains and determine how they can prepare for water risks in the age of climate change, set time-bound measurable goals for improvement, equip farmers, and invest in water conservation technology. And they must simultaneously cut their greenhouse gas emissions across their supply chains and operations. Agriculture’s large carbon footprint is a key contributor to the very erratic weather that’s driving financial risk in the food sector and threatening global food security.

Let this season’s monstrous hurricanes serve as a wake up call. Food companies must make water management a business imperative like never before.